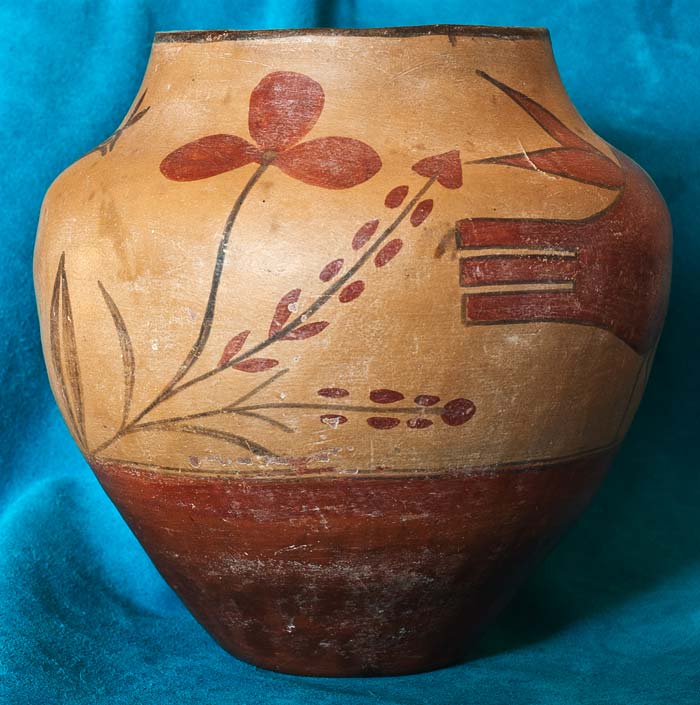

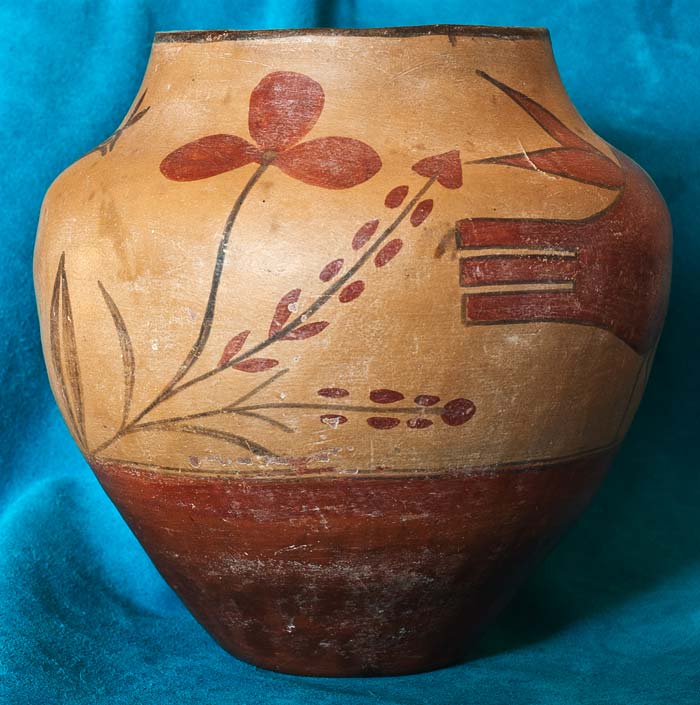

Zia Pueblo Pottery

Vintage (Circa 1920) Zia Bird Jar from the

Prof. Edwin Wade Collection

A Zia Bird Jar with Mocha-Tan Slip, c. 1920s

Among the most impressive features of this jar is its eloquent shape,

featuring a short upthrusting concave neck and extreme kerfed underbody.

This superb vase form is perfectly complemented by the oversized red painted birds

whose chests swell upon the vessel’s bulging shoulder and whose heads recede

upon the vessel’s narrowing neck. This expertly calculated matching of image to

sculptural form gives a three-dimensionality to the composition and

a charming visual vitality to the striding budgies.

Equally successful is the use of a tan rather than the typically stark white

slip of most Zia ollas. The warm caramel tone promotes a softened and subdued

relationship between the background and the richly cinnamon-colored birds,

lowering the contrast in value so that the birds can stride across the slip as a

harmonious rather than primarily contrastive compositional element.

The vessel was used, as is shown by small chips on the rim and abrasions

to the body. Someone loved this vessel enough to make it part of daily life,

and that someone was likely not an Anglo owner. The type of wear we see here

is commonly associated with Native use and frequent handling (Anglos employed

such vessels as flowerpots or lamp bases, causing a different kind of wear).

It’s tempting to imagine the potter kept this one for herself,

enjoying the company of her own creative genius.

Edwin L. Wade, Ph.D.

Vintage Zia Bird Jar Top View

Vintage Zia Bird Jar Top View

Vintage Zia Bird Jar Bottom View

Vintage Zia Bird Jar Bottom View

Vintage Zia Bird Jar Side Views

Vintage Zia Bird Jar Side Views

Vintage (Circa 1920's) Zia Bird Jar

Vintage (Circa 1920's) Zia Bird Jar

from the Professor Edwin Wade Collection

This is a large pot measuring over 9" Tall / 9" in diameter

and about 29" in circumference.

The pot is in Excelent Condition with most of its life spent on collector's shelves.

There are no cracks or dings. The pot when very gently tapped makes a pleasant solid

sound proving its integrity.

It is a thick wall pot... about 1/4" and clearly made for use. However,

those days are long gone. This pot is now retired and belongs in

a Collectors Cabinet.

Price $3250

<><><>

FYI Recent News - Sotheby Photo of $2.2 Million Ding Bowl

Recent News - Sotheby Photo of $2.2 Million Ding Bowl

The vessel’s rarity and authenticity is said to have supported its multi-million dollar sale price.

Recent News - Sotheby Photo of $2.2 Million Ding Bowl

The vessel’s rarity and authenticity is said to have supported its multi-million dollar sale price.

By the same standards, Pueblo ceramics should be among the most expensive pottery in the world.

At the time when the “Ding” bowl was produced, the Northern Song Dynasty was populated by about 50

million people, more than enough mass to support tens of thousand of artisans. In the 1890s, when

this bowl (see image below)was fabricated by the San Ildefonso husband-and-wife team Florentino and

Maxamilliana Montoya, the population of the pueblo had shrunk to a mere 110 souls. Out of this

number fewer than half were women, and of these women fewer than 10 were potters. A similar

situation existed through out the Pueblo world of the 1880s. The federal census recorded for

all 19 villages was a mere 7,762 people.

<><><>

More Dr. Wade comments about Pueblo Pottery

Not all Pueblo women made pottery, and not all who did possessed the same levels of talent and skill.

It’s not exaggerating to suggest that within any one generation only two master potters would emerge.

Historic Pueblo ceramics have commanded prices in the hundreds of thousands of dollars, and the names

Nampeyo of Hopi, Maria of San Ildefonso, and Acoma Mary have often been associated with pieces so valued.

But the vast majority of historic pots are priced significantly below $50,000 and most even below $10,000.

It makes no sense! There’s nothing comparable in world art, nothing more rare, and to my eye nothing

more beautiful than a skillfully sculpted Pueblo jar. How can it be that a handmade, hand-painted,

incredibly fragile earthenware pot a hundred and fifty years old can be bought for $3,500?

Two arbitrary factors have conspired to depress the Indian art market and to hamper recognition of the

traditions it celebrates and purveys as a true world art. First, Indians are close to us. A hundred and

fifty years ago many Anglo Americans dwelled in proximity to native groups and saw them as simply the

“poor folk living over there.” The idea that their superlative historic arts were vanishing and

needed protection, and that increasing rarity would increase these objects’ value didn’t register

except to a few museums and committed collectors.

The second and still handicapping issue is that anthropologists addressed native artworks as ethnographic

artifacts, as a bowl, a club, or a shirt, rather than as examples of a powerful and unique aesthetic.

Anthropological commentary was the equivalent of calling the Mona Lisa “an Italian woman in traditional

dress in front of a landscaped background.” The intellect is powerful, and our human desire to sort

and define is strong and useful. But, as the old song goes, “You’ve got to have heart,” and when

addressing art that surely is true.

I am happy to say that more and more art historians and connoisseurs have for some time been turning

their eyes to indigenous ceramic traditions, and, as they do, the unique brilliance of an elusive

aesthetic is being justly celebrated.

I often hear someone ask “Why are these pots so expensive?” Well, you know, they aren’t. In fact

they are so inexpensive that a world-class collection of world-class art objects can still be built,

and some far-sighted individuals are presently building them. Would you rather buy a $2,200,000 teacup

or an entire collection of vanishing American women’s art? You know my choice. Ed Wade.

Vintage Zia Bird Jar Top View

Vintage Zia Bird Jar Bottom View

Vintage Zia Bird Jar Side Views

Vintage (Circa 1920's) Zia Bird Jar

Recent News - Sotheby Photo of $2.2 Million Ding Bowl The vessel’s rarity and authenticity is said to have supported its multi-million dollar sale price.